“I want you to sample Juvenile’s ‘Slow Motion’ for this one. I don’t want it to sound like a drill beat, so slow it down. And make sure it’s got hi-hats in there.”

That’s Philly rapper Cashier Fresh, telling Alice Brnz what he’d like his next beat to sound like. It’s about 9:30pm on a weeknight in November, and the pair have been seated for hours in the dimly lit A-Room of a New York City studio that calls itself Cash Only Deli. “A lot of people make laptop music—but beats need to sound good in cars and venues,” producer Lord Sean, who’s been sitting in on the session and is pleased with Brnz’s work, comments at one point. Brnz—who, from plugg to NY drill to obscure requests like these, can just about do it all—cooks up what Fresh has envisioned in less than an hour. Fresh quickly maps out his flows and records across several takes, while Hammie Salem, the studio’s manager, pops in, nods along in approval, and signs the track off before the pair move on to the next record.

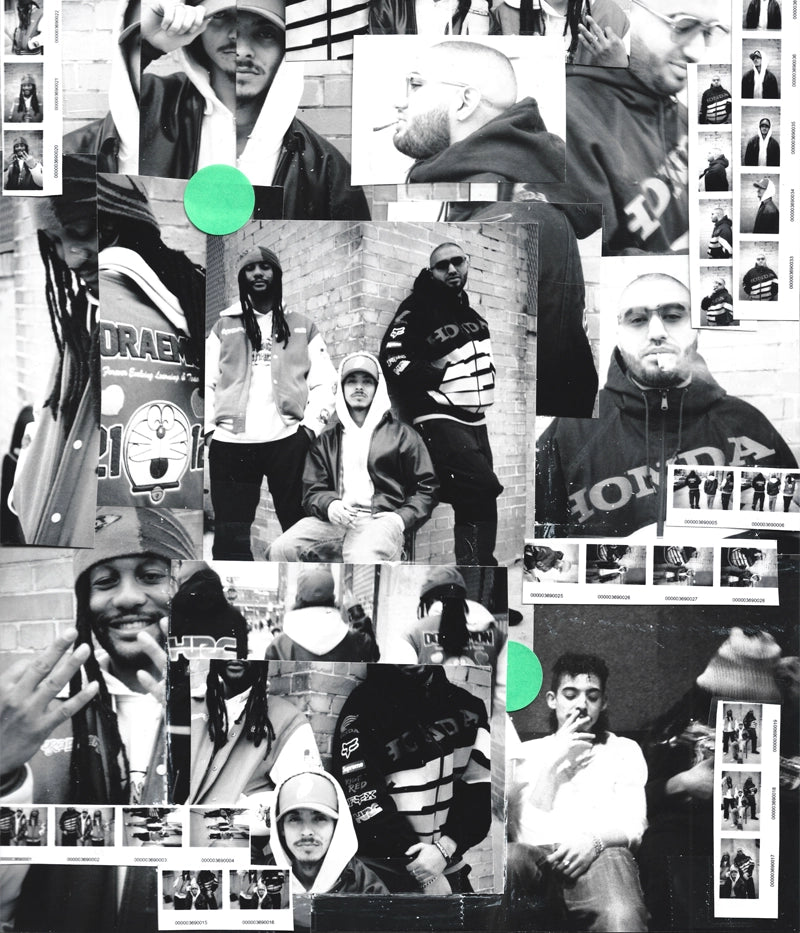

What’s happening here, in its mundanity, is atypical of the average New York City recording studio. A space that’s smaller than some bedrooms, the walls are adorned with manga shelves, skateboard decks, retro video game trinkets, and a custom graffiti mural acting as an official flag. On any given night, upwards of eight people will cram inside to work or observe. This, plus a small ISOVOX booth, bare bones tech, some sofas, and a flatscreen TV playing cartoon reruns are what make Cash Only.

After the COVID-19 pandemic pushed Brooklyn rap act Flatbush Zombies to move to Los Angeles—and in turn abandon their lease at Bushwick’s My HUB Studios—three longtime friends who’d been working closely with the group chose to bet on themselves. Inheriting the studio’s lease in September 2020 to establish Cash Only, Salem, a Brooklyn native raised up in the city’s skate and streetwear scenes, stepped in to manage the space with Brnz, who’d established himself locally as a go-to producer, engineer, videographer, and graphic designer, and RGR, a budding experimental artist who blends elements of hyperpop with raspy vocals. “This is very much for artists by artists, first and foremost,” says Salem. He, Brnz, and RGR do it all while sustaining their respective hustles to stay afloat, from Salem helping his father run a food truck to Brnz and RGR freelancing creative projects and working retailing gigs: “It’s just the three of us,” Salem says. “From paying the rent, to booking sessions, to producing audio and visual content in-house, to marketing, promoting, and managing—we’re an independent operation.”

Before they founded Cash Only, the group unanimously felt that there were few, truly open DIY recording spaces for New York City’s rappers, citing pricey Manhattan spaces and closed-door collective-run studios as the main options. “It's always been cliquey out here,” says Brnz, who at one point in our conversation stresses that any artist, of any genre, is welcome at Cash Only. “[The] goal is to establish a sense of community here—a family tree, a home, a mothership kind of thing, a real label.” Local artists like Donnie Durag, Boz Kamara, and G-BABY GVVAAN have notably cultivated their sounds there, while the likes of Delaware’s Quadie Diesel, Atlanta’s 10kDunkin, KEY!, and MuddyMya, and Detroit’s Zelooperz routinely drop in. Since opening its doors, Cash Only has expanded to include an adjacent B-Room to regularly host its in-house producers (Asa, Lord Sean, Brilliant).

What makes Cash Only Deli the most promising New York City mainstay for independent artists goes beyond clever branding (an infectious “Maybe they only accept cash” soundbyte being one of many elements in their cohesive storytelling) and connections to local scenes and groups like the Zombies. From the founding trio’s fierce commitment to the DIY ethic and lofty expansion goals, to their extended circle’s experimental and heterogeneous musical leanings, there’s something organic percolating behind the studio’s open—always rotating—doors. “The work I’m the most proud of is mostly stuff we haven’t even dropped yet,” Brnz tells me, noting that a Cash Only compilation mixtape is currently being polished for release.

Below, Brnz (Dev Evans), Salem, and RGR (Roger Peña), piece together Cash Only’s origins, its significance to New York City’s musical ecosystem, and the heights the studio turned all-encompassing label operation hopes to reach.

THE BEGINNINGS

HAMMIE SALEM: I feel like it all started at our friend BEK’s crib, in Park Slope. The house was two floors, and the bottom floor was a studio. It was a big space, with a couch, a table, some speakers. Tiled floors. That was the worst thing when it got really cold, those tiled floors. But the floors allowed us to cook, with neighbors not having an issue with it. I lived 15 minutes away, so I would just pull up and take photos and videos while Dev [Alice Brnz] and Roger and everyone else would put stuff together. At the time, Dev was dropping stuff on SoundCloud, and Roger was managing the Flatbush Zombies’s studio over at My HUB Studios—Roger made sure the equipment over there was okay, made sure everything was clean, made sure they were getting their stuff off, etc.

HS: That's when me, Dev, BEK, and Roger had the conversation to keep things going and move in there, and that's when I kind of stepped up to become a manager. We took up the lease, put down the deposits, and utilized the equipment the Zombies had left behind for us—it was bare bones equipment. They took the stuff they wanted and they basically left us a shit ton of other random stuff. So we moved everything into the space we’re sitting in now in September of 2020.

RGR: What’s wild is that around that time, I’d moved to L.A. for a little while to be with the Zombies, to continue my work with them. By the time I came back, about three months later, Cash Only Deli was already a well-oiled machine. Dev had already made his contacts within the floor of the building and there were people coming in and out of our space. He started getting into his engineering, his producing, and it's been blossoming since.

HS: Dev was running sessions. All of us were working on reaching out to local rappers, big time rappers outside of the city, just everyone we knew really. Like, ‘Yeah, we have a studio here in New York. We have space for X, we have time for Y, Dev knows how to engineer. Roger was working on his own music as well. He was in the space all day, back when we didn’t have our B-Room. Everyone was polishing their chops, and that first year was straight grinding.

ALICE BRNZ: I tapped in with my friend Asa, who I’ve known since he was thirteen. We used to make beats together—and I remember running into him right around the corner from here, near that restaurant called Sea Wolf. I told him that we’d secured the spot, and he decided to join in. We started co-running sessions. Asa went to school for audio production and engineering, so he brought a certain professional programming to the space.

HS: Everybody started going back and forth and they were just cooking, and cooking, and sending out beats, and getting artists in here, and grinding. Dev was pushing his music. Roger was pushing his music. We were open, and we were here to work.

A NORTH STAR

AB: What we're trying to have happen this year, as a goal, is to establish a sense of community here. A family tree, a home, a mothership kind of thing. A real label. Because it's always been cliquey out here in New York.

HS: It's always been cliquey. Who knows what any of our careers, our lives, could have been like if there was a space like this early 2010s. If someone had pulled me to the side, to learn music publishing, learn this, that, and the third. Or if someone pulled Dev to the side and taught him engineering, taught him how to use ProTools. If someone pulled Roger to the side to help him with songwriting… If we had that, maybe things wouldn’t be as fragmented out here.

RGR: The best way to sum up what they both said is that for New York, or even for this region, we want Cash Only to be the door that people step through, whether it be in the beginning of their careers or at the climax of it. And we want it to be for everybody—for a while it was like, if you're making drill music, you're Uptown, if you're making alternative, you're in your room in bumblefuck New York, you're in Long Island. Growing up in the 2010s and seeing how A$AP Mob was, you had to go through an A$AP tie to get a beat or whatever. They had their own studio. They had their own producers. You had to go through them. Everybody had their ‘I need to do it my way,’ mentality, and there wasn’t much else.

AB: Right now, I make a lot of beats and I engineer for mad different people, extremely different kinds of artists. Working with Cash Only and what we’re trying to cultivate, I feel like there's just more adaptability. I have to be a chameleon, because over here, we don’t make a certain kind of beat, a certain kind of music. We try to serve everybody as much as we can. Take Roger and Fresh—two of our artists who make extremely different kinds of music solo, but have also made tons of songs together here.

HS: The thing is, since we're all born and raised in New York, that alone is leverage enough for building relationships because anyone who's from out of town wants to come to New York and tap in with a native. They want to see the sights, they want to go where we go, eat where we eat, hang out where we hang out, record where we record. Being at the epicenter of the epicenter, it's kind of this great honor—and burden—on all of our shoulders. It’s why everybody comes to the city to make music, to establish themselves, and we wanted to be at the forefront of that. We felt like we could really do the city a great justice being those people and being the place to be. And of course we’re still being paid our worth, but we’re not that major studio where artists are going to spend thousands upon thousands upon thousands of dollars to record in the city. And with the system Dev has built, we’re developing artists too.

Cash Only is akin to a bedroom studio, but it still functions as a professional setting where music is being made at a high output. Now that we’ve been going for a while, we see that the cheat code is the physical space, because it's a tangible thing. It’s a place to make connections, a North Star for artists in and out of town. We’ve got multiple producers working here, like Sean, Birthday, Asa. We have a DJ we call Momo who’s making sure the music we make here gets spun out there in the world. We’re not trying to be boxed in, because we are essentially a record label now, and it’s not just a hip-hop record label even with a lot of rappers coming in. We are a New York record label. Any music that’s being made in New York, that’s good, we’re in it. And if we’re not in it, we’re going to be in it. And if we're not going to be in it, we’re encouraging them to tap in with us.

THE EPICENTER OF THE EPICENTER

HS: Back in Spring of 2021, we took a group trip to Atlanta to make some connections, which started a real pipeline. Social media is a great tool, especially if you know how to use it. We got looped into a few group chats, Twitter, etc. We were linking with all these different artists that we’d been listening to all these years.

AB: I feel Da$H is one of those people. I used to listen to Da$H a lot when I was younger. It’s just surreal to be able to just call him up to show him beats, or have sessions with someone like KEY! We all used to listen to KEY! Going to Atlanta and really being able to work with him and see him in his full genuine environment was crazy. Atlanta is a city that’s all about what we want to cultivate in music—a community. That’s the spirit we want to bring to New York. I got to meet Jace. We did a joint for Quadie, who’s from Delaware, when he was out in Atlanta too. We met up with MuddyMya, who recently came up here to record some joints. We had 10kDunkin in here too. Me and Sean got a few songs with him. Beyond Atlanta, we’ve got Fresh in here constantly from Philly. We’re a floor full of producers and we're all getting it done full circle, reaching out to artists, managing the space, making the music.

RGR: This whole thing is a fucking blessing, but it's also really crazy. I can't front, it's a challenge in itself that has made me better as an artist. I've had moments where I feel like I can't make shit, and then me and Dev or Blue start something, and it sticks. It’s because of what we’ve built over the last couple of years.

HS: The goal for next year is kind of just more follow up, more rigid structure of just getting things done, getting things out. We want to be more of a well-oiled machine. You know, we're all such good friends, and we all get frustrated with each other a lot. We also have to hold each other accountable. Dev talks to me about what I should be doing better all the time—I've never done this management stuff before. He told me two years ago to be headstrong, to just jump into it. Learn as you go, figure it out. I fuck up a lot, but he helps me get on track and then at the same time, Dev has his habits that I help him get a hold of. Roger, same thing. Me and Roger being such old friends, we're not perfect, but I don't know. We trust each other.

As someone who doesn’t make music, there are a lot of arguments I have with others about financial and business stuff, because it’s so hard to make tangible money in this business. I have to constantly figure out how to make sure people are getting paid, people are getting their worth. And then we have to constantly figure out how to brand and market artist’s ideas, and maintain our relationships with others. And while this past year put a lot of pressure on us, 2024 is going to be so busy, with so much coming out. I feel like it'll fall into place.

AB: Keeping up productivity on a day-to-day basis can be mentally challenging. Sometimes there's nobody sitting here telling us to do anything, you know what I mean? But we have to achieve it somehow, you know what I mean? Having output is a thing. Enough beats in the backlog, recording enough music, so we can plan things. There’s always more calls to be made. There's always more artists to work with because there's more artists every day.

RGR: We can only do so much with getting people in this room, and if we want to instill that community aspect we have to branch out: That means events, venues, traveling to different boroughs and cities. There’s a lot to be done.

HS: The moment is here, and we’re at the forefront of something. We're ready to work. We're ready to show the world what's been going on here. The whole thing is a cool blessing, even when it gets hard. We’ve all got day jobs. I help my father run a food truck, I've worked retail. Roger has worked in marketing, retail, so has Dev. Dev does so much freelance work. Graphic design, video work, everything.

And we still manage to be here most days of the week, which has become a lot easier now that we have a B-Room. It’s like a home away from home. And honestly, more than anywhere else, I'd rather be here.